When I was a girl, there was a woman on TV ads, Peg Bracken, who hawked for Birds Eye Frozen Vegetables. “I’m Peg Bracken, and I wrote the I Hate To Cook Book,” she would tell viewers. Bracken advocated for ease in the kitchen, spending as little time as possible over a hot stove, and leaning into the newly available and heavily advertised “convenience” foods, which were all processed in various ways.

Many of the new conveniences, including microwaves, freeze-dried food, and synthetic fabrics were around thanks to military research and development. Now that WWII was over, business could elbow in and convince people that they had been working too hard, and, thanks to the military-industrial complex’s inventions, they could now kick back and enjoy some leisure time.

Conveniently, TV rose to prominence in roughly the same period, creating an easy way to pump advertisements for all these new wonderments directly into people’s homes and brains, and to create an addictive avenue—sitting and staring at a screen!—for the leisure that was allegedly made possible, in beautiful circular fashion, by all the modern conveniences.

Sociologists John Robinson and Geoffrey Godbey collected data in an ongoing project called the Americans’ Use Of Time Project. For more than thirty years, starting in the early 1960s, Robinson and Godbey had study subjects record how they spent their time. Leisure time underwent an incredible transformation from the 1960s to the 1990s. In the ‘60s, people would engage in hobbies and social activities, such as handwork, woodwork, gardening, visiting with friends and relations, bridge, and playing games together. From 1980 on, the top two leisure activities were watching TV and shopping, which would toggle back and forth in any given year for the first- and second-place slots.

So we started spending money and sitting more, as our world filled with extra gadgets and conveniences. Later doodads that entered everyday life thanks to military R&D were the internet, GPS navigation, super glue, and computers.

Now our cars take us everywhere, we carry around the Great Library of Alexandria in our pockets, our streaming services ensure we never experience a moment of boredom or downtime, and yet we’re fatter, more depressed, more addicted, more suicidal, and more diseased than ever. We live longer, yes, but, collectively speaking, our extra years are often unhealthy. Many people nowadays spend a decade or more, thanks to obesity, diabetes, lymphedema, arthritis, etc. barely able to move from Point A to Point B on their own steam.

I don’t call this progress. I call it misery.

When I think about authors and thinkers from the past 15 years whose ideas have directly influenced my life, Katy Bowman is always on that list. Bowman is a biomechanist, something I had never heard of before I encountered her work. Bowman identifies varied, healthful movement and seeks to correct patterns of movement (or non-movement) that can cause dysfunction or pain. She writes about “nutritious movement,” which includes walking, hanging from bars or tree branches, and many other exercises and motions that keep us limber and able to optimally meet physical challenges in our lives. Just as a nutritious diet is varied and includes many healthy options, a nutritious movement diet is broadly varied too.

Her work is an antidote not only to our habits of sitting and making love to screens all day, but also to the idea and practice of engaging in an hour of daily “workout”, which creates the illusion that we’ve sufficiently met our movement needs. Of course, it’s not that easy. The human organism is designed to move in diverse ways all day long.

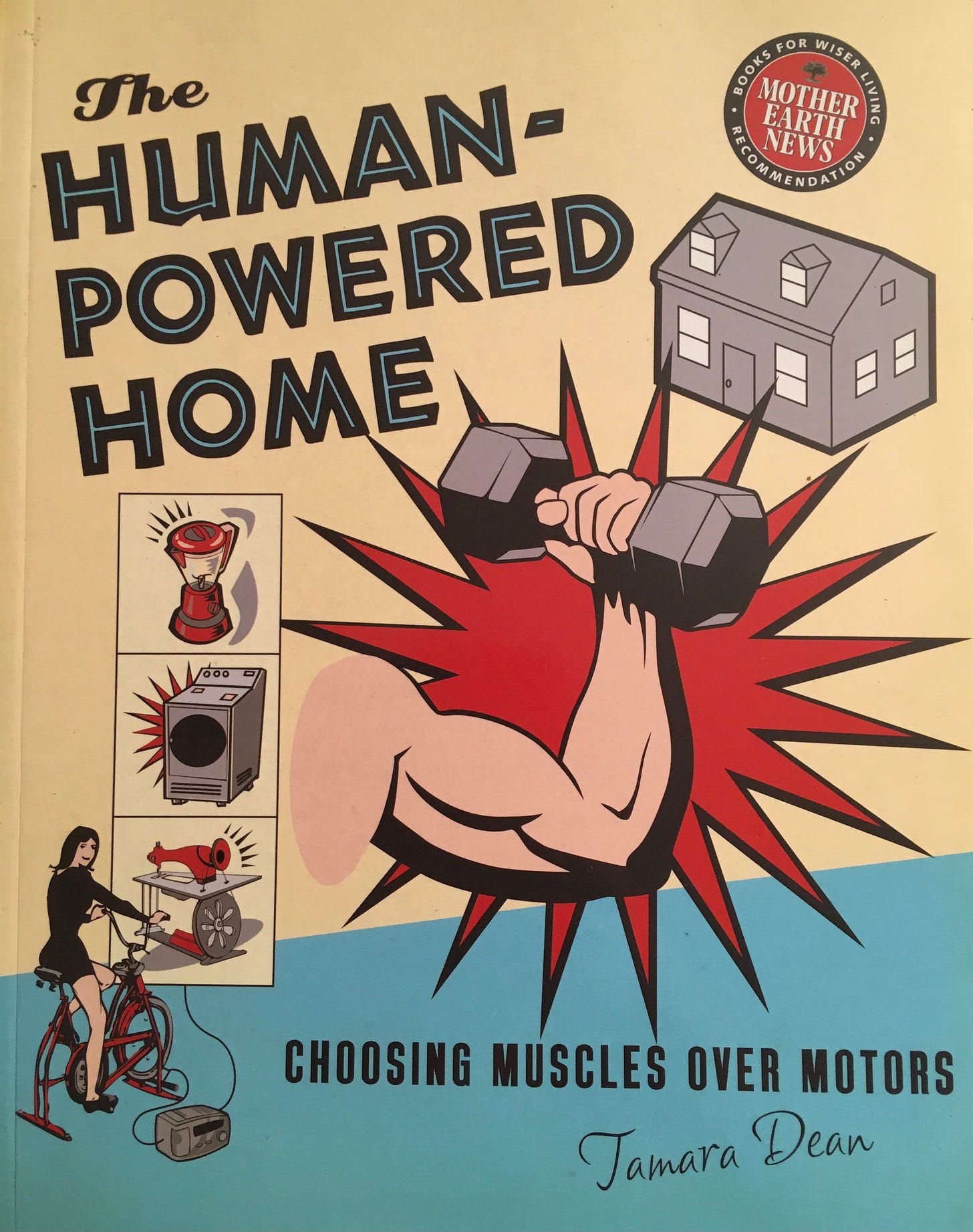

Not that long ago, one important way that we used to regularly get movement was by doing things for ourselves rather than relying on the machines that populate our lives for everything. In the kitchen, there were grain and food mills and pasta makers that you crank by hand; hand-powered nutcrackers and can openers; and beating batter with a wooden spoon. My kids used to love to use a mechanical egg beater. They used to be easy to find in thrift stores. I haven’t seen one in years, despite looking every time I go to EcoThrift. (Although you can buy a new “classic” eggbeater on Amazon for just under $30.)

People walked or biked or rode a horse to get places. They hung clothes out to dry, and hand-washed dishes. Daily life required varied, frequent movement.

When it comes to this sort of stuff, I grew up in a hybrid household. My parents raised dobermans, and we had an electric can opener to open dog food cans, but we also had a push mower. We had a microwave, but my mother baked bread every week. I think we were a transitional generation, making the shift from using human muscle power to perform tasks and create goods to using machines to do everything or to simply buying ready-made. I didn’t get a dishwasher until we had five children. But, today, with a much smaller household, I still use a dishwasher. It’s interesting how, once modern conveniences take root in our lives, it really takes a conscious decision to step back and analyze whether they’re necessary as circumstances and priorities and awareness change. Or as we conclude that we can save electrical energy, incorporate more movement and less sitting in our lives, and reframe a “need” as a want with the liberation that promises by simply doing more stuff without machines and gizmos.

I recently read The Comfort Crisis: Embrace Discomfort To Reclaim Your Wild, Happy, Healthy Self. The author, Michael Easter, contends that we would benefit by voluntarily sidestepping the constant climate control, abundantly over-available calories, and many fixtures, such as streaming services, pills and alcohol, and comfort foods that allow us to exist in a particular kind of stupor: We’re not exactly satisfied—it’s difficult to be satisfied when there is no perceived earning of the satisfaction—but it’s not quite clear what we’re wanting or needing or missing. Easter says that we know something is off, we don’t describe ourselves as happy, but we can’t really bring ourselves to turn our backs on all the Doordash and Amazon deliveries.

Author Easter ends up doing extreme exercise in 100-degree weather; getting dropped off deep in the Arctic tundra to hunt caribou for a month; and intentionally experiencing hunger. I found it all intriguing, but I’m advocating something a bit more accessible: Let’s consider places in our lives where we might do various somethings using our own muscle power.

All of this doing and making was what life was composed of for our grandparents. I had two different ravioli makers in my cabinets—one a kind of ravioli rolling pin and the other a two-piece, ravioli-making system--both of which were used incredibly infrequently. My grandmother and my aunt—who ravioli’d much more often—used to just cut the pasta or ravioli by hand, no cranked pasta maker, no ravioli gadgets, just a single sharp paring knife. So much of our modern convenience—and the tendency to acquire so much stuff—is simply an expression of consumerism. My ravioli-making doodads certainly were.

Who benefits from our dependence on the gadgets and the machines? Everybody who sells the machines, or parts for the machines; every entity that sells energy to run the machines; and all the Mad Men who advertise for the machine makers. They do not have our best interests at heart.

Interrogating what really serves us, versus what simply robs us of space and of more opportunities to move and make and undertake a worthwhile endeavor, seems hygienic and liberating. It offers the possibility of an elemental education in where things come from and how things are most simply done; how we don’t have to be slaves to our machinery. It’s good medicine for adults and children both.

For anybody who wants to optimize movement for health and wellness and sense of purpose; for people who like making things and appreciate the things that others make; for people who would like to decrease their dependence on fossil fuels and increase their skill base; for all these folks and more, this kind of inquiry can have a deep value and lead to a lot of fun places.

I think the idea of Convenience Uber Alles has been a contributing factor in fewer children being born in the U.S. There’s one narrative that says that children are a burden, they impede freedom, they’re a lot of work, they’re often inconvenient. Much of that is true, of course, but it misses the big picture and the real point: For those who want children, the dimensionality they add to life is enormous and enlivening. There may be a bigger picture, broadly speaking, to the entirety of our lives. What if walking, experiencing temperatures beyond 68-72 degrees, spending time outdoors, using our muscles instead of machines to do things, and embracing many and various movements every day had a larger meaning? What if it made us healthier, more connected, and less dependent on The Man? Wouldn’t that be something?

I'm an Orthodox Christian, and we practice fasting for about half the year. We fast almost every Wednesday and Friday and have longer fasting periods for Lent and the Nativity. For most people this looks like refraining from meat, dairy, and eggs (some people eliminate oil and wine as well) on those days. I was reading a book about fasting when Russia was mostly Orthodox, and I was surprised to read they fasted from a number of things including conviences and entertainment. It has really inspired me to broaden my views on fasting to potentially include refraining from television watching, smartphone use, and maybe eventually doing our laundry the old fashion way or using a wood burning stove during fasts. I think confining it to a certain time makes it feel more achievable. Also, I think it alligns more with the traditional spirit of fasting which was supposed to be difficult, uncomfortable, and inconvient. It also just seems to be a healthy way a living physically and spiritually whether or not someone is Orthodox!

I reread Brave New World this week so your post is very relevant to what I've been think about lately. Mainly, our modern culture of valuing comfort, pleasure, and conformity above all else.