War

My undergraduate thesis was a biography of Dorothy Day, founder of the Catholic Worker Movement (CWM). I was drawn to writing about her for many reasons, primary among them that she walked her talk.

College was a lot of things, including a systematic experience of respected adults letting down their youthful fans in one way or another. Here’s one example: Some friends went to Vermont to visit eco-anarchist author Murray Bookchin, to discuss with him the ideas he laid out in his books for a better world. They found him eating ham sandwiches (despite advocating for vegetarianism in his writing) and driving to a store that was a five-minute walk away, kind of a big ecological no-no for an eco-anarchist.

Similarly, I was excited when feminist author Mary Daly came to campus to speak. I knew from her writings, including her book, Gyn/Ecology: The Metaethics of Radical Feminism, that she had left Christianity behind, but I also knew she had been Catholic. I thought she would have an interesting perspective on my thesis topic. I went up to her after her talk and told her I was writing a biography of Dorothy Day. She replied, “Why would you do that? What was good about her?” She pointed in turn to the three fingers of her left hand with her right hand pointer while she said, “She was a woman, she was a woman, she was a woman.” Then she pivoted to the next person waiting to speak to her. I found that kind of intellectually lazy; wasn’t it “good” that Dorothy Day had actually taken actions in real life that helped poor people and alleviated suffering? I also felt at the time, and I feel it even more strongly today, that it was an unfortunate missed opportunity for an elder to say, “Nice work, youngblood!” or to somehow offer encouragement. I.e., Mary Daly elevated women in her work, but here was a real-life young woman standing in front of her and she had nothing to offer.

So to encounter in Dorothy Day an adult whose actions were consonant with her words felt both inspiring, rare, and borderline amazing. Day had founded the Catholic Worker Movement in the 1930s with a New York colleague. America’s Great Depression had impoverished millions of people, many of them visibly living on the streets in New York City’s Bowery. Day and her co-founder, Peter Maurin, established modest Catholic Worker houses in New York to house and feed people who were struggling. They lived in the houses alongside those they sought to help. Dorothy Day interpreted literally the corporal works of mercy laid out in the gospel of Matthew (Feed the hungry, house the homeless).

Catholic Worker houses (and ultimately farms) popped up all over the United States as the movement grew. Then WWII happened. The organizing voice of the movement was the Catholic Worker newspaper, which Day published and editorialized in from New York. She was a committed pacifist during WWII (again, literally interpreting the commandment “Thou shalt not kill”), which was a deeply unpopular position. Catholic Worker houses around the country began to shut down or dissociate from the movement because of Day’s stance of unwavering pacifism. By 1945, two-thirds of Catholic Worker houses had closed, and the Catholic Worker newspaper had lost more than 100,000 in circulation.

At the time, I really wasn’t down with the idea of absolute pacifism, although I respected the courage and conviction Day exhibited with her consistency. I adhered to the necessity of “just war,” the idea that war is always to be avoided, but sometimes it remains the best choice in a dreadful situation.

I’m having a harder time with just war these days, mostly because diplomacy just doesn’t seem to be on the menu any more. My understanding is that one of the principles of determining whether a war is just or not is that it is the option of Last Resort. Every possible avenue has been exhausted before turning to war.

Have you ever been in a meeting where a decision has to be made and there are two apparently opposing ideas clashing, preventing resolution or forward motion? I have. And I have also occasionally seen individuals in these settings who listen to everybody’s viewpoints and eventually speak up and say, “I understand and appreciate what each of you is saying. I think I see some common ground here and a possible way forward.” I don’t have that excellent skillset, but I’ve seen it in others. It’s unusual and precious, and absolutely essential on the world stage. I haven’t caught a whiff of it on that world stage in a very long time.

When I started writing this piece a couple of days ago, my understanding was that my country was actively involved in five conflicts: in Yemen, Syria, Niger, Somalia, and with the Houthis in the Gulf of Aden. Then I read an article in the New York Times this morning, which made clear that we’re also in conflict with or militarily present in Iraq, Iran, and Jordan too. That already seems excessive. But we’re also bankrolling two major conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza.

It doesn’t feel like there has been a lot of evolution in conflict resolution since the Cold War ended. Are we really doomed to relive a repeating cycle of war, death, destruction, maiming? We’ve become more technologically advanced, with a vast array of horrific weaponry, but we’re no better at getting along with one another. In Dante’s Inferno, the fifth circle of hell was reserved for those who were incorrigibly bellicose and wrathful during life. Their eternal fate is to fight each other in hell forever. While the Inferno and Purgatorio are organized around different sinful behaviors, Dante built his Paradiso (which, granted, is less fun to read than Inferno, but still) on the four cardinal virtues: Prudence, Temperance, Justice, and Fortitude. I’m really not seeing “leaders” that display these virtues. And you can dismiss Dante as a 14th-century relic, but can we allow for the possibility that there might be some consistent human vices and virtues? And that growth and maturity —both as individuals and as a society—might suggest that we have the potential to move more in the direction of the virtues and further from the destructive vices? Why does that not seem to be happening?

I was funded in the 1980s to record oral histories of women peace campers in England, Italy, and Japan. The women had set up encampments outside military bases to protest the presence of the bases, but also to protest war in general. At that time, there was a very popular, evolved women’s opposition to war. It essentially argued that mothers do all this work to raise up decent, healthy human beings, to nurture and nourish, only to have those humans, upon entering young adulthood, run the risk of becoming cannon fodder for conflicts they have little or no role in, fighting against the thoughtfully raised and nurtured children of mothers from another part of the world. My own belief is that the task of nourishing and nurturing often falls to women, or is embraced by women, whether or not they are mothers.

I hate the environmental degradation and cultural destruction of war; I hate its half-life in the form of PTSD, of lingering cluster bombs that continue to maim and kill civilians more than fifty years after we dropped them, of grief, of unnecessary disability and morbidity; I hate all those lives cut short; I hate the economic ruin it leaves in its wake, except for the Congressional representatives and defense contractors who enrich themselves at a very high price that others pay. But I just can’t imagine the sorrow and misery of losing a child in war, whether a combatant or an innocent victim of “collateral damage.” My heart goes out to everyone who experiences that sorrow and misery. I believe it so often doesn’t need to happen.

Theologian Reinhold Niebuhr criticized what he considered pacifism’s inability to take seriously the real world of political power and international violence. I get it, Reinhold. We live in an armed and hostile world. Just war doctrine offers the possibility of applying moral standards to international violence. Here’s the sticking point for me: I just can’t shake the feeling that we’re living in a world full of active global conflicts that have little or no claim to being “just.”

And I’m finding it harder and harder to square a belief in just war with the unequivocal directive of Thou Shalt Not Kill. Not a lot of wiggle room there. Whether you’re religious or not, I think many people view the Ten Commandments as pretty reasonable guidelines for a functional, civilized society. What I once viewed as Dorothy Day’s naivete and intransigence has begun to seem like a hard line in the sand to protect life on earth and urge us to become better versions of ourselves. Maybe a humane way forward rests somewhere between that position and an authentic and rigorous embrace of just war principles. But if we can’t actually apply and adhere to the just war doctrine, I favor the hard line in the sand.

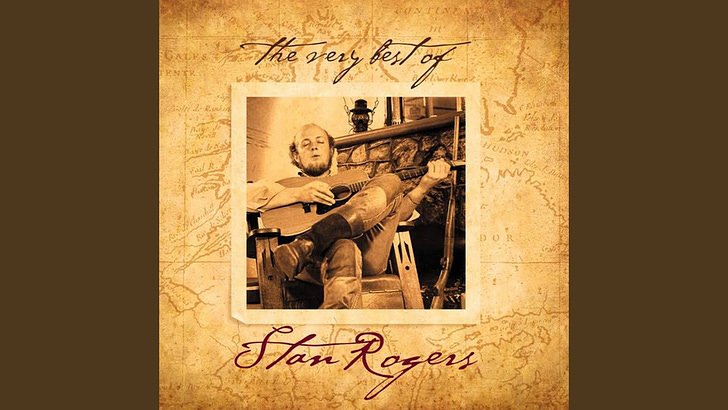

Here's my favorite anti-war song:

And I really like this one too: